Peter Oliver was interviewed for this story before the COVID-19 crisis forced the closure of non-essential businesses in Ontario. On March 16, Oliver & Bonacini (O&B), the hospitality group Oliver co-founded, temporarily closed operations across Canada except for three locations currently offering take-out. O&B has subsequently co-founded SaveHospitality.ca, an advocacy group of independent Canadian restaurant owners lobbying the three levels of government on rent abatement, supplemental employment insurance, forgivable loans and other measures. Peter’s son Andrew Oliver, O&B’s president and CEO, says O&B has given away food to its most at-risk staff, and, besides advocating for enhanced EI for employees, is doing what it can to be able to bring everyone back when it’s safe to do so. “O&B will survive,” says Andrew. “But it’ll be extremely painful and we’ve had to make tough decisions to ensure that.”

Peter Oliver was interviewed for this story before the COVID-19 crisis forced the closure of non-essential businesses in Ontario. On March 16, Oliver & Bonacini (O&B), the hospitality group Oliver co-founded, temporarily closed operations across Canada except for three locations currently offering take-out. O&B has subsequently co-founded SaveHospitality.ca, an advocacy group of independent Canadian restaurant owners lobbying the three levels of government on rent abatement, supplemental employment insurance, forgivable loans and other measures. Peter’s son Andrew Oliver, O&B’s president and CEO, says O&B has given away food to its most at-risk staff, and, besides advocating for enhanced EI for employees, is doing what it can to be able to bring everyone back when it’s safe to do so. “O&B will survive,” says Andrew. “But it’ll be extremely painful and we’ve had to make tough decisions to ensure that.”

By Tracy Howard

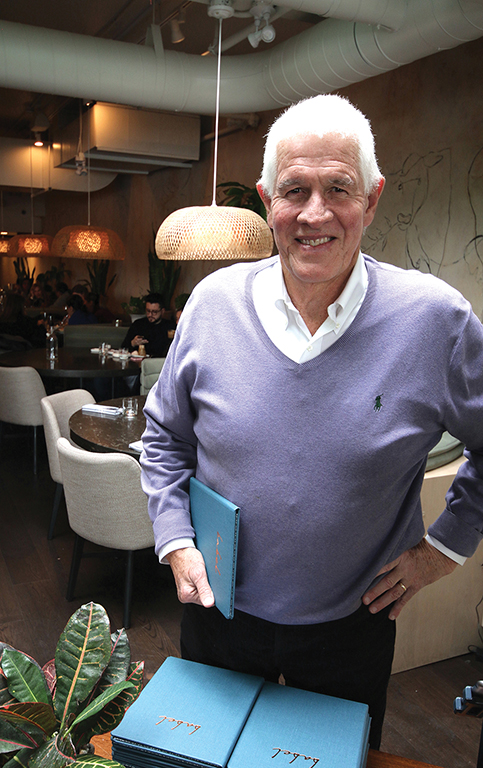

Peter Oliver doesn’t often do interviews but when asked how long he has to discuss the Leacock Foundation, the charity he heads that helps economically challenged youth in Toronto and South Africa, he responds: “whatever it takes.”

While the 71-year-old co-founder of Oliver & Bonacini (O&B) Hospitality is retired from the day-to-day operations of one of Canada’s leading restaurant and event groups, he’s hardly twiddling his thumbs. Oliver helps train staff in new locations on O&B’s values and mission, and also leads awards presentations to long-serving employees. Additionally, he recently completed a five-year tenure as national chair of a $40-million campaign for JDRF Canada (formerly the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation).

“I believe if you’ve done well, you have a debt to pay and that’s what makes society stronger,” Oliver says. “I would take it even further and say for every citizen, the drive should be you’ve got to put in more than you take out.”

But Oliver admits in his salad days, philanthropy wasn’t a focus. “I was too young, I was building a business, starting a family,” he explains. The Oliver family includes his wife, Maureen; their kids, Vanessa, Jessica, Andrew and Marc; and seven grandchildren. Andrew, 35, is O&B’s president and CEO.

Entree to Canada

In 1967, Oliver left his native South Africa to attend McGill University in Montreal. The attraction to Canada was more practical than poetic. After prep school in England, he decided North America was his “next place of adventure,” and discovered university was less expensive here than in the U.S. At the time, his parents had a farm in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and could only subsidize half of his first year’s tuition.

Graduating with a commerce degree in 1971, Oliver returned to South Africa, but, with few business prospects there, moved on to England. When the U.K.’s struggling economy proved challenging, he travelled around Spain. Eventually, practicalities set in. “I’ve got to get stuck in and I need some money,” Oliver remembers thinking. “Maybe Canada’s not so bad.”

Back in Montreal, he worked as a stockbroker and was eventually transferred to Toronto. After a few years, Oliver began selling commercial real estate, which proved to be a valuable background for future restaurant deals.

As for his entree to the food industry, Oliver paints a colourful picture. “I was lying on a beach in Rio sitting next to this bus driver from New York,” he recalls. “He sort of convinced me the thing to do was have a business where the cash register could be going ka-ching, ka-ching while you’re lying on the beach in Rio.”

Oliver says he was inspired by a successful food shop he’d noticed that offered a product he thought he could improve upon. “I was going to put a manager in, hopefully make an extra 25,000 bucks a year and continue with my real estate,” he relates.

Building the business

Building the business

Oliver’s Old-Fashioned Bakery, located near Yonge and Eglinton, opened in 1978 and had a long run as one of midtown Toronto’s go-to casual-dining spots. Oliver quickly found himself becoming absorbed in the food business. “Money wasn’t the only factor, building a business was important,” he explains.

Next up was Bofinger, Oliver’s homage to a Parisian brasserie of the same name, which opened in 1986. The restaurateur calls it “one of the biggest mistakes of my life.” It was challenged by unkind reviews and the fact it was a huge space, with rent and taxes to match. Bofinger wasn’t Oliver’s sole financial misstep. “I nearly went under three times,” he says. The first time was in 1981 when he’d spent over a million expanding Oliver’s Bakery, and the bank called in his loan. Fortunately, North York’s Auberge du Pommier, the restaurant he opened in 1987 inspired by a restaurant he and Maureen had visited in rural France, has been an enduring success.

The partnership with Michael Bonacini began in 1993 and, as is common with Oliver’s business decisions, was born out of a real estate opportunity. A space had become available in Toronto’s downtown Commerce Court complex and Oliver negotiated a rare deal in which the landlord paid for everything. After his original partner dropped out, Oliver approached Bonacini, who was executive chef at the city’s then red-hot Centro. Oliver offered the Welsh-born Bonacini 35 per cent of what would become Jump and, rather than having the chef put any money in, asked him to take a small pay cut for two years.

“I didn’t then have to worry about anything to do with the kitchen or the food quality,” Oliver says. Next for the duo came Canoe, now marking its 25th year on the 54th floor of the Toronto Dominion Centre. At that point, Oliver — who’d by then sold the bakery and Bofinger — offered Bonacini a part of Auberge du Pommier, and O&B was born.

The company now has more than 65 properties, which takes into account venues in which it has a substantial interest, such as individual event spaces and a Calgary restaurant group. Oliver credits his son Andrew with the expansion outside Ontario, including locations in Edmonton, Montreal and Saskatoon. Andrew, far from being handed the keys to the kingdom, was initially tasked with invigorating O&B’s flagging event business. Within 18 months, it became the fastest growing part of the company.

Although proud of the accomplishments of his son and the rest of the leadership team, Oliver’s clear about the path he and Bonacini forged. “We did a lot of the hard work establishing the basic culture and values of the company,” he says.

Giving back

In 1984, at age six, Oliver’s daughter Vanessa was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes, a milestone that seemingly ignited his philanthropic impulse. For a time, he handed over the daily operations of his company and threw himself into chairing the Toronto chapter of JDRF.

With his money tied up in the business, Oliver had to find creative ways to raise funds. He decided to live atop a flagpole for a week “flogging” raffle tickets, which earned $250,000. Over the years the flagpole stunt ran, it raised more than a million dollars for JDRF.

The Leacock Foundation began in 1992 as the Leacock Club when Oliver banded together with some friends to raise money for each of their individual causes. It’s named after Stephen Leacock, the acclaimed Canadian humourist who was also a McGill professor. The friends eventually decided to focus on helping at-risk youth in Toronto. (Oliver’s co-founders have since died. While the foundation’s board now has 13 people, Oliver remains the main fundraiser.) Inspired by the Oxford Union, the Leacock Club holds an annual debate, which is now used as a fundraiser. Other funding is sourced from grants, such as from the Ontario Trillium Foundation, an annual golf tournament and donor gifts.

In Toronto, the Leacock Foundation supports extracurricular and summer literacy and leadership programs in three of the city’s high-priority communities. When asked about a video focused on the foundation’s summer leadership camp, which mentions that some Toronto youth have never experienced nature, Oliver gets fired up. “Poverty is pitiful! How little exposure many of these kids have to things children should have exposure to if they’re going to become productive. Surely that’s what we should aim for, that all citizens have the chance to succeed.”

While the Leacock Foundation’s work in Toronto connected Oliver to the needs of his adopted hometown, in 2001 he attended an event that moved him deeply as a South African. Nelson Mandela, in this country to receive an honorary Canadian citizenship, appeared at a fundraiser at the Toronto home of power couple Gerry Schwartz and Heather Reisman. “In Mandela’s presence, I realized I was in the same room as somebody unique,” says Oliver. Mandela spoke about the need in South Africa, and Oliver says he wondered who in the room would actually help out. “Then I asked myself: Well, what will you do? And that was it, I went to South Africa. I said I’m going to get involved in education, and it’s one of the best things I’ve done.”

After telling the foundation board he wanted to broaden its mission, the concept of a “Triangle of Hope” was formed. It involves linking underserved Toronto schools and their counterparts in South Africa with Toronto private schools. For example, every year 16 girls in grade 11 from Branksome Hall visit South Africa for two weeks and are paired with local students their same age. “It’s one of the most emotional experiences the Toronto girls have had,” Oliver shares. “Especially because they’re exposed to poverty, and they’ve never seen real poverty.”

In South Africa, the foundation started investing in the Get Ahead Project (now QGAP), an independent low-fee primary school, which had about 350 students and was having good academic results. The school is in rural Queenstown in the Eastern Cape, the country’s poorest province. To ease the long commutes faced by some students, the Leacock Foundation helped build a satellite primary school 40 kilometres away in Whittlesea. In 2007, the foundation helped start a Get Ahead secondary school in Queenstown.

The foundation has invested more than eight million dollars and built 46 classrooms in South Africa. Emphasis is placed on the students’ well-being and developing individual strengths, with creative and STEAM learning (science, technology, engineering, arts and math) integrated into the curriculum. Oliver reports their use of technology is the highest among schools in Queenstown.

But he pulls no punches about the obstacles. “It’s absolutely shocking the extent to which corruption and incompetence are dragging the country down,” he says. In addition, because of recent drought and high unemployment, many parents are struggling to pay the modest tuition. As a result, Oliver says the foundation is making a fundraising push for scholarships.

Despite the challenges, there’s little doubt Oliver will continue helping kids. He speaks proudly of the foundation’s accomplishments, the fact it will never spend more than 10 per cent of what it raises on administration, and that donors can choose whether their money goes to programs in Toronto or South Africa.

“In general, if we all put in more than we take out, there will be more than enough for people who can’t cope,” he says.

The Leacock Foundation responds to the pandemic

Led by restaurateur Peter Oliver, the Leacock Foundation addresses the inequality of opportunity for youth facing challenging economic and social conditions in Toronto and South Africa.

But Kristine Gaston, the foundation’s executive director, advises that due to the COVID-19 crisis, they’ve had to temporarily stop programming in Toronto and the Get Ahead Project (GAP) in South Africa has had to close its schools during the lockdown.

“Lack of technology at home, language barriers and cramped living conditions make it difficult for children to participate in online schooling,” advises Gaston.

In response, the foundation has partnered with First Book Canada to distribute 300 workbooks and reading materials to kids in Toronto’s Woburn community and will do the same in the two other city neighbourhoods it supports. Additionally, the Leacock Foundation’s social media channels are offering daily activities and resources to keep children engaged in learning. In South Africa, the GAP team is providing educational resources through Facebook, as well as communicating potentially life-saving information to parents and caregivers.

To find out more and to donate, visit leacockfoundation.org or call 416-489-9309.

Additional Details for Toronto Hospitality Assistance

Key Statistics

• In 2019, Toronto restaurants generated more than $7 billion in annual revenues. Collectively, there are more than 100,000 people employed at these restaurants.

• The hospitality industry is Canada’s 4th largest employer, employing 1.2MM people

• Estimated $20 billion in direct loan payments are due April 1, 2020

• Of 2MM Canadians laid off, 300,000 are in Ontario’s foodservice industry alone

Loan Program

• Government subsidisation through forgivable loans would help with impact currently felt and anticipated for months to come

• Amounts would be calculated based on the net revenue of the previous year of the company. Suggested rate is 10% subsidy to cover 8 weeks of closures. Beyond 8 weeks, the subsidy would continue at 1.25% of previous year net revenue.

• The loans would be paid back through HST and Payroll Taxes generated through gradual reopening of the business

• Liquidity to cover operating costs is paramount right now. Said loans would provide the immediate

• Similar programs with government-backed loans are being rolled out in the U.S. and Denmark providing industries such as the hospitality industry with greater flexibility

Rent Assistance

• In the interim, governments can step in to endorse a rent freeze until a loan program goes into effect.

Wage Subsidy

• The federal government’s announcement of a 75% wage subsidy for businesses who have seen a 30%+ decline is unfortunately not applicable to vast majority of foodservice that cannot open or provide work for all or the majority of their staff.