What is family foundation governance and why do we need it?

By Gena Rotstein

Family foundation governance is as much about how decisions are made as it is about communicating the decisions made. This article outlines the key components around family foundation governance. Even if you don’t have a formal foundation structure, you can use many of these concepts around family philanthropy conversations.

In the book entitled, Managing the Family Business by Thomas Zellweger he identifies three reasons why family firms need governance. These same reasons apply to family foundations, family councils or granting committees for Donor Advised Fund (DAF) accounts:

- Articulating the motivations of the founder.

- Help with decision making, especially around “sticky” challenges like engaging spouses and in-laws.

- Moving beyond the traditional mechanisms associated with family foundation governance (block voting v. individual voting) — for families with multiple branches allows for individual voices to be heard.

In Canada there is more than $1 Billion tied up in multi-generational family foundations where by the inheriting generation is struggling to either meet the funding objectives of the founder, or have become disinterested in the family philanthropy program resulting in those funds being managed by a third-party with limited or no input from the family. Imagine what would happen if that $1B of trapped capital was unlocked? One way to prevent this number from increasing is to set up the family inheritors for success from the outset.

Focusing on the key factors associated with family foundation and family philanthropy governance and decision making we begin the exploration by understanding the lifecycle of a family foundation moving into the overall governing structures and ending with managing family dynamics.

The lifecycle of the foundation:

The first step is to understand the lifecycle of the family foundation. Just like any organization, there is a natural timeline for a family foundation. For some families, foundations are established to be run in perpetuity. The ongoing nature of this type of foundation means that it will continually cycle through a re-birth stage as the needs of the community and the decision makers’ values evolve. For other family foundations the intention is to sunset the foundation after a specific period of time. Regardless of your timeline, establishing some guidelines for giving and decision making will make the job of future generation(s) easier.

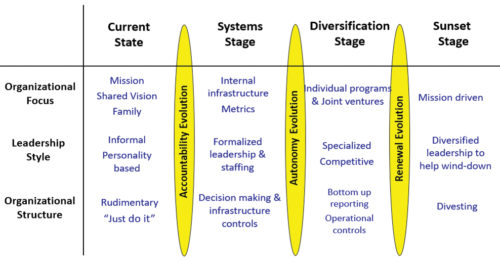

In the figure below (adapted from CentrePoint Non-Profit Management) shows the lifecycle of the foundation. It is not about how long the foundation has been in existence, rather it is about the infrastructure that supports or encapsulates it.

A foundation may be in the start-up phase for multiple generations because of how decisions are made and projects are executed. As the foundation takes on more structure it goes through an evolutionary cycle. Another thing that affects the lifecycle of the foundation is the lifecycle of the family member(s) who set it up and continue to manage it. Personal and career lifecycles directly impact the rate, timing and effectiveness of the foundation’s evolution.

A foundation may be in the start-up phase for multiple generations because of how decisions are made and projects are executed. As the foundation takes on more structure it goes through an evolutionary cycle. Another thing that affects the lifecycle of the foundation is the lifecycle of the family member(s) who set it up and continue to manage it. Personal and career lifecycles directly impact the rate, timing and effectiveness of the foundation’s evolution.

As the foundation evolves the impact is felt in its focus, its leadership culture and the formal structures that support the mandate and the leaders. For some, the evolution rotation might be simple and painless, for others these evolutionary blips might be more challenging. One way to mitigate the struggles is to understand how the evolution will impact you, the leadership and the foundation overall, and when the timing of the evolution will coincide with your personal lifecycle.

As the foundation moves from one stage to the next, the governance will also move along the continuum. The Start-up Stage has basic governing documents and decisions might be made at the kitchen table or during pillow talk. The Systems Stage may be when the Next Generation of leaders are on-boarded and decisions are spread across multiple family members. The Diversification Stage when, depending on your size and mandate, might include engaging external advisors and paid staff. At this point, if the organization is operating in perpetuity, it likely will do a recalibration to assess its relevance and engagement of the family. If continuing on, it may move back to an early stage to explore new areas of funding or new partnerships. If the board decides to wind things down, or the founder wrote a sunset clause into the governing documents, it is in this last stage, Sunset Stage that assets are liquidated to other charities and foundations. For some this divestment is to a community foundation, for others there might be instructions written into the documents as to which organizations will benefit from the funds. Just like the previous evaluations there will be pressures put on the culture and operations of the foundation. This is okay and to be expected. A well-planned sunset stage means that decisions can be made and emotions and history honoured at the same time.

Governing principles:

In 2004 the Committee on Family Foundations of the Council on Foundations released a report outlining the different governing principles that guide family foundations. When you map these governing principles against the lifecycle stages of the foundation you will see how these principles are enacted will depend on the evolutionary stage of the foundation.

These principles take into account the culture, size, proximity and areas of interest of the individuals who make up the Board of Directors or Trustees. How these principles are put into practice determines the right type of governing model best suited for the foundation.

Strategic or operational?

At the core of this question is how hands-on do you want to be: the more hands-on, the more operational. This approach is ideal for those who do not have staff, have smaller budgets or who do not have a formal structure that holds your philanthropic dollars. What this looks like in practice:

- A governing board that establishes the mission, guides the operations, oversees the effectiveness of the grants and acts as a connector between family members;

- Responsible for reviewing the mandate of the foundation to make sure that things are still on track and that the granting and investment strategy are aligned with the mission;

- Allocates sufficient human capital to meet the programming and granting objectives;

- Succession planning; and

- Communicates with the broader family and the advisors as to the performance of the foundation.

Individualized giving through the family foundation/fund?

Ideally the founder and the founding board members have laid out what role and how much individual family members can influence the granting and investment strategy of the family foundation. Laying out the way that individuals can share their opinions and drive the conversation is a key component to the governing documents. Even without a foundation, how family philanthropic assets will be invested is a critical discussion point. What this looks like in practice:

- Board identifies the types of people that they want sitting on the board — characteristics, skill-set, experience, family or non-family, etc.;

- External advisors are welcome

- Terms for the board are set and communicated broadly to the family. These bylaws are established and guide how people are on-boarded, trained and removed from the Board;

- Roles and responsibilities are clearly articulated;

- Meetings are held regularly to ensure fiduciary and mission oversights;

- Individual family members can submit grant requests that are outside of the mission, however the entire board reviews these types of applications and a formal budget is set to not exceed a maximum dollar amount or percentage of total giving; and

- Training and continuing education is made available for all board members and external advisors.

Collective Impact, Joint Ventures and Strategic Partnerships – What does this look like?

Many foundations recognize that they can’t move the dial alone. That said, good family foundation governance has a way for making decisions around who, when, under what circumstances and how to collaborate with other funders or facilitate a multi-stakeholder solution. What this looks like in practice:

- Actively seek out opportunities to learn about best practices and compare practices with others in the field;

- Have a diversified funding portfolio that includes traditional philanthropy, debt financing, unique funding models like Social and Community Impact Bonds, multi-year funding, challenge grants and endowments;

- Has a fund for emergency funding for organizations that have a long-term relationship with the foundation;

- Have a publicly stated Theory of Change so that applicants understand where and how their project can best fit in the philanthropic vision as well as where and how other funders might fit into the funding continuum;

- Share successes and failures publicly. Highlight lessons learned from the granting process and the evaluation process;

- Ensure that the funding does not undervalue the staff remuneration. Remember, it is impossible for 100percent of funds to go the project, someone has to turn on the lights, pay the rent and cover the paper in the printer;

- Map out your Time, Talent, Treasures and Ties – what else do you bring to the table other than your pocketbook? Can you provide technical expertise or link this organization to others who can help with that line item?;

- Convene conversations with industry experts and leadership; and

- Engage in public policy conversations as permitted by law.

Fiduciary responsibilities – Is it more than just reading a financial statement?

Aside from giving money away (which is likely the best part of running a foundation), one of the most important jobs of the Board is understanding how your assets grow and what your giving horizon looks like. One of the most important roles of the Board is to ensure that there is prudent fiscal oversight. What this looks like in practice:

- Know and ensure your foundation is in compliance of the tax laws;

- Understand your expenses and what is a reasonable proportion of operation costs to donations;

- Board members should not be compensated for their time with a few exceptions such as: travel to meetings, reimbursement of reasonable expenses associated with conducting the duties of the foundation (i.e. site visits). These exceptions should be documented in the foundation’s governing documents;

- Family members may be employees of the foundation and they may also hold a position on the board. As stated above, this must be documented in your governing documents and employee compensation must be justified to the market and have a job description along with performance objectives and evaluations;

- Ensure that due diligence is conducted on grantees

- Ensure there is a written investment policy;

- Establish and oversee the internal financial controls and record keeping;

- Approve the operating and disbursement budget and ensure that the investment strategy will meet these expenses;

- Retain an external firm or accountant to review the financials annually. For larger family foundations you might want to consider having a separate audit committee; and

- Share the financial information with the family members.

Managing family dynamics

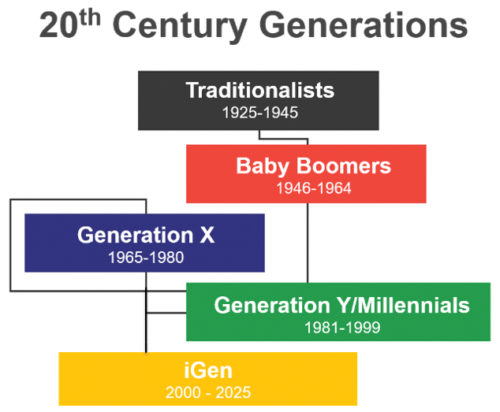

To understand family dynamics, one should understand the history of the family. Today, in Canada there are five generations that are influencing the family wealth discussion. Those individuals who were born during the Great Depression through to those who are born today. With almost 100 years at the family wealth table it is no wonder that personalities, values and family dynamics are a strong force.

As the image suggests (source: Johnson Centre), not only are there five generations at the family wealth table, but three of those generations overlap. This overlap is due to blended families and later childbirth. In some cases you will have Baby Boomers with Gen X children and Gen Y children; you will also have Gen X children with Gen Y, Millennials and iGen kids; and you will have Gen Yers with iGen. Imagine being born when the telephone wasn’t ubiquitous having a conversation with someone who was born with a Smart Phone in their hand? Now imagine the pace of the conversation and how this pace influences what is discussed, how communities are built, how societies evolve and how politics play out.

As the image suggests (source: Johnson Centre), not only are there five generations at the family wealth table, but three of those generations overlap. This overlap is due to blended families and later childbirth. In some cases you will have Baby Boomers with Gen X children and Gen Y children; you will also have Gen X children with Gen Y, Millennials and iGen kids; and you will have Gen Yers with iGen. Imagine being born when the telephone wasn’t ubiquitous having a conversation with someone who was born with a Smart Phone in their hand? Now imagine the pace of the conversation and how this pace influences what is discussed, how communities are built, how societies evolve and how politics play out.

It is for this very reason you cannot expect family groups to vote as a block let alone share the same interests and values. “Family firms [foundations], and by extension their owners [founders], do not only strive for financial goals. The goal set of the family first prominently includes a concern for reputation and transgenerational control and for benevolent ties within and among the family, the firm, and community stakeholders.”

As an individual sets out to establish their legacy they ask themselves, their partner(s), and their children questions about:

- Their core values;

- A vision for the future of the family and the society;

- Confronting mortality and time horizons;

- The lifecycle of the family and family business/wealth — growth or harvest mode;

- Shared urgency between the desires of the founder, the needs of the community and the passions of the inheritors; and

- Desired participation of their children and grandchildren.

These existential questions are at the root of any philanthropy plan. Even when that philanthropic structure is established as part of a tax and wealth planning tool. We know that taxes and tax incentives don’t motivate people to give, but using the tax structures that are available makes planning easier and, depending on how the conversation is structured, moves the flow of capital from the foundation out into the community more effectively.

Effective family governance can help navigate some of the sticky conversations around favouritism, harmony, and glass ceiling. These symptoms of family dynamics are not only found in the family business, they also manifest themselves around the family philanthropy table. By acknowledging these symptoms and using the guiding principles to shape the policies and procedures for decision making the foundation leadership establishes a strong base for ongoing activities beyond the founder.

Lifecycle + governing principles + family dynamics = Impact

The governance of your family council, family granting or full family foundation is more than just about the policies and procedures. It is the glue that ties the founder’s motivations with the desired social impact across the generations. Starting out with an end in sight and understanding the lifecycle of your foundation will allow for you to adopt the principles that will guide you through its evolution and manage the family dynamics that will shape the conversations.

Gena Rotstein is a CoFounder of Karma & Cents.